The Home Office’s presentation of the facts about immigration detention is open to question

This blog comes from Detention Forum volunteer Gareth, who tweets at @garethglynn. The image is from @Carcazan.

Hot on the heels of the Windrush scandal, several damming reports and a lot of unwanted media attention, the Home Office has published a fact sheet on its blog pages that details its ‘approach to immigration detention’.

The Home Office explains that it blogs ‘on the latest topical home affairs issues. It features a review of leading media stories, responses to breaking news, rebuttal to inaccurate reports, and ministerial comment.’

The fact sheet makes some statements that merit scrutiny – these are shown in bold type. Below, these are compared to available data plus reports, observations and comments from independent parties.

Realistic and reasonable?

When we do detain, in each case, we must have a realistic prospect of removal in a reasonable timescale.

The Home Office detains people who are ‘liable for removal’, as well as for the purpose of establishing people’s identity. But successive sets of immigration data cast doubt upon how ‘the realistic prospect of removal in a reasonable timescale’ is assessed when Home Office case workers decide whether to detain an individual.

What the Home Office considers ‘reasonable’ isn’t spelt out in its blog, but chapter 55 of the Home Office’s Enforcement Instructions and Guidance defines ‘imminent’ as 4 weeks.

55.3.2.4 In all cases, caseworkers should consider on an individual basis whether removal is imminent. If removal is imminent, then detention or continued detention will usually be appropriate. As a guide, and for these purposes only, removal could be said to be imminent where a travel document exists, removal directions are set, there are no outstanding legal barriers and removal is likely to take place in the next four weeks.

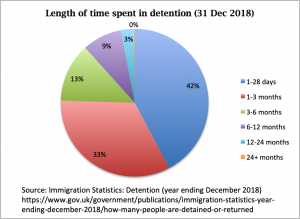

However, the most recent immigration statistics show 58% of people in detention were held for longer than 4 weeks. One person had been detained for 774 days – just over 25 months. This data implies that many people are being detained without a ‘realistic prospect of removal in a reasonable timescale’.

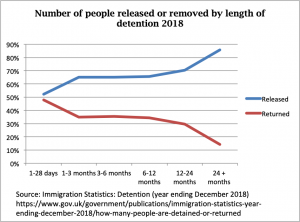

In fact, the number of people returned to another country from detention has fallen steadily over the past 6 years. Since 2015, fewer than half of all people detained have been removed or deported. In 2018, only 44% people were returned from detention; the majority were released, in most cases their detention having served no purpose.

And detention gets less effective the longer someone is detained. 48% of people leaving detention within 28 days or less are removed or deported from the UK. For people detained longer than 28 days, this drops to 35% or less. By the time someone has been detained for 2 years or longer, they are very unlikely to be returned.

According to immigration lawyer Colin Yeo, the ‘declining number of removals suggested a “detain first, ask questions later” approach … something is wrong with Home Office information on who is removable and who is not.’

The Home Office is regularly found guilty of breaching its own guidelines. Giving evidence to the Home Affairs Committee, Hugh Ind, Director General of the Home Office’s Immigration Directorate, admitted that ‘Sometimes, in retrospect, we are found to have made the wrong judgments. There are some very difficult judgments included in making an assessment of a realistic prospect of removal within a reasonable timeframe.’

Access to legal advice

Those detained are advised of their right to legal representation, and how that can be obtained.

While individuals may be advised of their rights, the Joint Committee on Human Rights report published in February found ‘problems with the availability and timeliness of legal advice in detention.’

Immigration detainees should have better and more consistent access to legal advice to challenge their detention. Moreover, the substantive immigration cases themselves are often not within scope of legal aid. This may cause problems because an individual’s detention is inherently linked to their underlying immigration issue. It is also inefficient and may well be costly, as matters repeatedly return to court (creating unnecessary costs for the taxpayer), and decisions about an individual’s immigration status are delayed.

In November 2017 the Bar Council, which represents barristers in England and Wales, expressed major concerns about immigration law and its administration. Crucially, its report Injustice in Immigration Detention found that ‘many people struggle to secure the free legal representation they need to challenge their detention in court.’

Celia Clarke, director of Bail for Immigration Detainees (BID) says ‘We have repeatedly raised concerns about the dearth of legal advice in detention and the devastating impact of the 2013 legal aid cuts which removed all non-asylum immigration work from the scope of legal aid … individuals are not able to access the legal advice they need at an early opportunity and are forced to make late submissions in desperation.’

Vulnerable people

In September 2016, we put in place the ‘adults at risk in immigration detention’ [AAR] policy as a key part of the Government’s response to Stephen Shaw’s first review of welfare in immigration detention.

The policy strengthens the presumption against detention for vulnerable people to ensure that individuals are not detained inappropriately.

Under the ‘adults at risk in immigration detention’ policy, vulnerable people are detained, or their detention continued, only when the immigration considerations in their particular case outweigh the evidence of vulnerability.

A survey of almost 200 people held in seven UK detention centres on 31 August 2018 showed that almost 56% were defined as an ‘adult at risk’. And independent monitors and inspectors have found numerous instances of vulnerable individuals detained inappropriately since the AAR policy was introduced.

The Home Office’s policy to protect adults at risk had not been effective in keeping many vulnerable people out of detention. There had been five deaths in or immediately following detention.

In our report on immigration detention, we found that the Adults at Risk (AAR) policy is not protecting the vulnerable people it was introduced to protect. Read the report and comments from Committee member @Stuart_McDonald here:https://t.co/SIYqMXwsU3 pic.twitter.com/8uBay2vqxG

— Home Affairs Committee (@CommonsHomeAffs) March 21, 2019

[T]he Adults at Risk (AAR) policy is not protecting the vulnerable people it was introduced to protect. Instead, the way evidence of risk is weighed against immigration factors has increased the burden on individuals to evidence the risk of harm that might render them particularly vulnerable if they were placed or remained in detention. The policy has significantly lowered the threshold for Home Office caseworkers to maintain detention of those most at risk. Rule 35, the process intended to act as a safeguard against the detention of vulnerable people by ensuring that particularly vulnerable detainees are brought to the attention of relevant staff, has failed to prevent too many injustices. It is not currently a fair or robust system.

Indefinitely

We do not detain people indefinitely.

The Home Office explains this by saying that it detains people for a finite but unspecified time during which there is a ‘reasonable prospect of their removal’ (see above). This interpretation of ‘indefinite’ seems to contradict the widely accepted definition offered by the Collins English Dictionary, among others.

- If you describe a situation or period as indefinite, you mean that people have not decided when it will end.

- Something that is indefinite is not exact or clear.

Many MPs have the same understanding of the term. For instance, Shadow Home Secretary Diane Abbott says ‘Ministers insist that detention is not indefinite, but if someone is in a detention centre, cut off from their friends and family, with no idea when they will be released, it certainly feels like indefinite to them.’

Likewise, Lib Dem MP Tim Farron says: ‘immigrants can be detained with no idea of when they might be removed or released.’

The Home Affairs Committee received evidence from Freed Voices, a group of experts-by-experience who have been in immigration detention in this country, on how the lack of a time limit can have a devastating impact on the emotional and physical well-being of those detained.

It is the absence of numbers – of facts, of certainties, of any plan or structure – that makes indefinite detention such a mental torture. At the start, you look down every possible rabbit hole to end the not-knowing. But after a while your brain begins to melt. You start to doubt yourself. I wanted to numb the pain. And that is why the rate of self-harm in immigration detention is so high.

Freed Voices

Conclusion

The facts listed by the Home Office may reflect the policy and rules by which it is bound to operate. But the factsheet presents an idealised picture. Outcomes, judged by both official stats and independent authorities, show the situation is markedly different in several important respects.