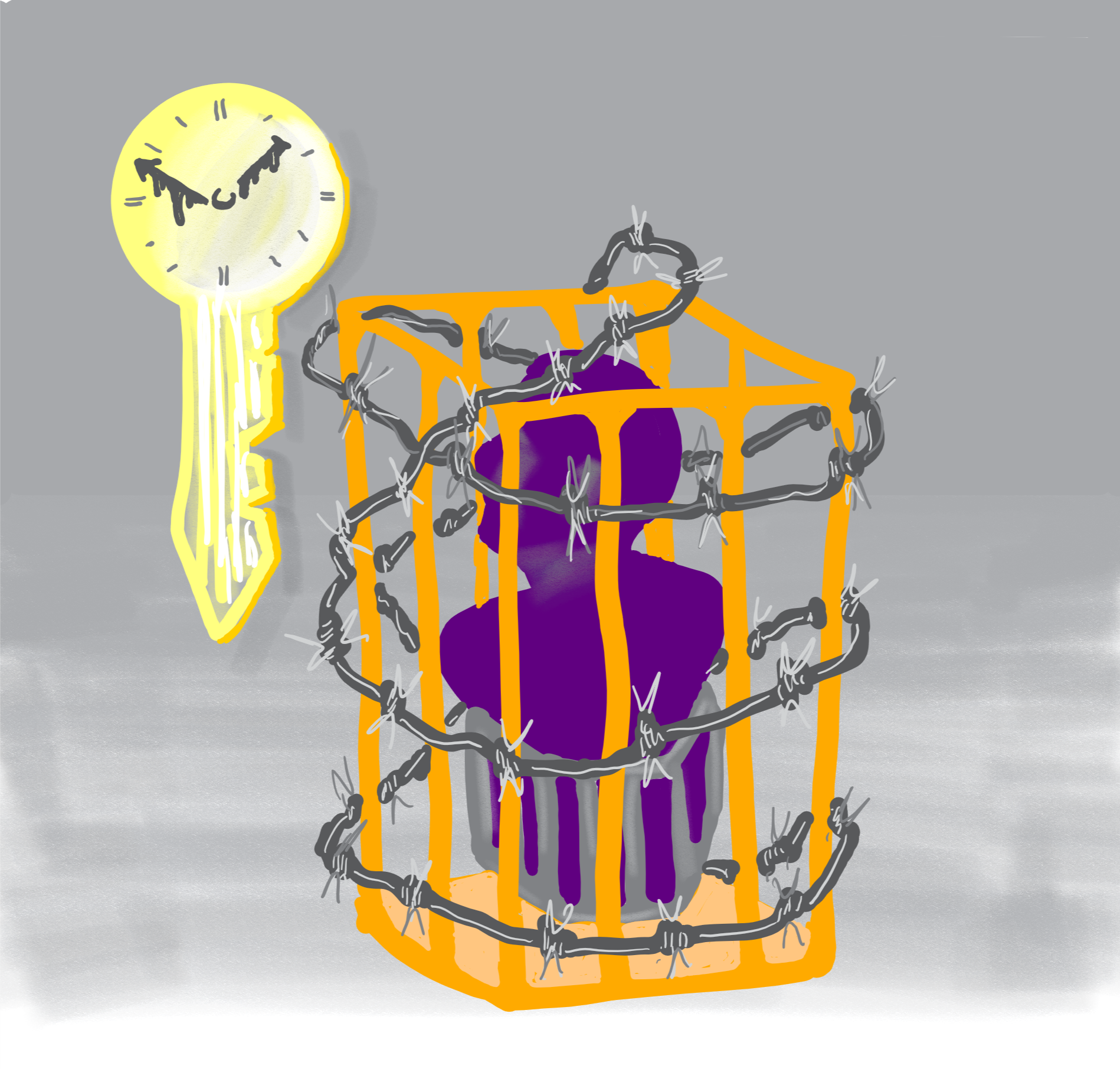

Image by @Carcazan

Just a few nights ago, I was flicking through a very old report by the Joint Committee on Human Rights published in 2007. Its edges are frayed. Some pages still have post-it notes stuck on them. 12 years ago, I was a director of an asylum NGO and this inquiry into the treatment of asylum seekers was the first occasion I came into contact with any parliamentary mechanisms. One of the Committee’s recommendations – that there should be a 28 day time limit on immigration detention – came to shape much of the work that the Detention Forum has concentrated on, in an attempt to radically change the UK’s immigration detention system.

In 2006, I was director of an asylum NGO. And this was my first experience of parliamentary “stuff” – we submitted evidence to this JCHR inquiry. It was also the first time a 28 day time limit on immigration #detention was recommended. #Time4aTimeLimit pic.twitter.com/jhP6ywVRwI

— Eiri Ohtani (@EiriOhtani) June 27, 2018

Of course at that time, I didn’t know that this recommendation in para 275 of the report was going to be so significant. Immigration detention was such a niche topic back then that hardly anyone ever talked about it in public, let alone politicians. Also at the time, I admit I was naïve. My field of vision didn’t extend beyond the written policies and procedures that seem to make up the bureaucracy of an immigration system. I thought as long as I kept on telling the Home Office policies and procedures are not being followed or that they are not good enough, things would be better. I never seriously thought about how politics, and for that matter, society in general was intimately connected with the work I was doing.

Fast forward 12 years, I am a very different person. And I am reading another report by the same Committee (different members, of course) on one of the most controversial scandals to hit the UK government recently: detention and deportation of the members of the Windrush generation. Much has already been said and written about this: racism, post-colonial amnesia and the fact that Theresa May’s Hostile Environment policy has been, quietly and devastatingly, destroying all parts of UK society. It led to the resignation of Amber Rudd: we now have a new Home Secretary, Sajid Javid.

The "systemic failure" at the Home Office is a direct result of government policy. People could have their cases resolved in the community, but instead are being routinely and indefinitely detained. #Time4aTimeLimithttps://t.co/Du9rBX4yXu

— Detention Action (@DetentionAction) June 29, 2018

And the scandal brought fresh light to the issue of immigration detention. Many people, who thought they were British were suddenly thrown into prison-like immigration detention centres. The Committee’s investigation focused on testimonies and case files of two people, Paulette Wilson and Anthony Bryan, whose stories were covered widely by the media and who gave powerful evidence to the Committee.

I haven’t had a chance read the report in full yet but the Committee’s summary is indeed strongly worded.

The key message from the Committee is that the detention of Paulette Wilson and Anthony Bryan did not happen because of a series of ‘mistakes’ but was a direct result of systemic failures of a very powerful department, the Home Office. And this department completely failed to act in a way that respects and protects their core human right to liberty. When the Committee reviewed their casework files, they discovered that none of the safeguarding mechanisms that the Home Office say they have in place to ensure the presumption of liberty worked. The Committee’s list of concerns is as follows:

- Information and evidence on the case file, which supported the individual’s account, was ignored;

- Family protestations were not heeded;

- Representations by MPs failed to elevate concerns;

- There were numerous different people involved in the handling of each file but all proceeded with the wrongful detention of those individuals; and

- There was inadequate oversight of these cases by more senior officials to guarantee that proper steps were being taken to ensure just and timely progress of the cases.

The truth is, for many of us working with people and communities affected by immigration detention, none of this came as a surprise. It is absolutely crucial to remember that what is happening to the Windrush generation, whose immigration status is being questioned, has been happening to thousands and thousands of others for years.

This report is welcome, but we can't afford to view #Windrush as an isolated incident. Every year tens of thousands of people are locked up without release dates. The whole immigration detention system needs to be overhauled. It's #Time4aTimeLimithttps://t.co/IWsrPb57hl

— Liberty (@libertyhq) June 29, 2018

Mass, routine indefinite detention of so many people is an intended result of government policy of punitive and coercive immigration enforcement. In a letter to the Home Affairs Select Committee, Sir Philip Rutnam, Permanent Secretary, chillingly describes that the strategic intent of enforced removals includes ‘signalling to the wider community that the UK exercises coercive powers an an enforcement back-stop for its immigration control.’ Putting the fear into the wider community by showing the state’s absolute might is what the government is trying to do and detention is part of this. Its human cost is incalculable. In addition, its financial cost is staggering. It costs over £30,000 for someone to be detained for a year. And the Home Office had to pay out more than £21m in compensation as a result of detaining more than 850 wrongly between 2012 and 2017.

850 lives irreparably damaged with long term consequences. #Time4aTimeLimithttps://t.co/PEdIDYpQNS

— TheDetentionForum (@DetentionForum) June 29, 2018

It doesn’t have to be this way. People can have their immigration cases resolved in the community. They can be properly supported and helped to navigate the labyrinth of the system. If they get good quality legal advice throughout, they are likely to get fair results more quickly. The Home Secretary seems to promise that he will reshape the Home Office and create a fair and humane immigration system. I hope he will take a bold move and put people at the heart of the system.

The Committee’s summary ends with this note:

‘The Committee intends to conduct a further inquiry into the UK’s immigration detention system in the Autumn, in which the Committee will consider concerns around the safeguards in the immigration detention system in the UK, including the UK’s lack of a set time limit to immigration detention, which is unusual.’

We welcome this new, fresh, inquiry into immigration detention as a whole because detention doesn’t just happen to the Windrush generation. We also welcome that the Committee will look at the lack of time limit in the UK’s immigration detention system. This open-ended approach to locking people up underpins the culture of impunity which encompasses the entire immigration detention system – and it has to stop.

It is rather unprecedented that two Committees, the Joint Committee on Human Rights and the Home Affairs Select Committee, will be conducting an inquiry into immigration detention at more or less the same time. Let us not forget that Stephen Shaw’s second review on immigration detention is to be published soon too. This intensity of activity just goes to show how badly a radical reform of the entire system is needed.

But it also tells us something else. Previous reports and inquiries have already recommended what should change about immigration detention: that there should be a time limit, that there should be a far more robust way of routing vulnerable people out of detention, that there should be an accessible and effective judicial oversight of the system, and that there should be more community-based alternatives. The frustration that reports after reports after reports is not leading to any significant change was what came across most strongly when we hosted a parliamentary meeting last year as part of our Unlocking Detention project. This is what Kasonga, an expert-by-experience from Freed Voices said.

"All those reports, whatever the focus, come to one conclusion: we need an end to indefinite detention, we need alternatives to detention" – Kasonga #FreedVoices #Unlocked17

— TheDetentionForum (@DetentionForum) November 16, 2017

"We speak out as experts, not as case studies."

Kasonga from Freed Voices, an expert by experience group, tell us how there is overwhelming consensus on introducing a time limit, and only using detention as a last resort.#Unlocked17 pic.twitter.com/lNfRNfd3nt

— Right to Remain (@Right_to_Remain) November 16, 2017

We now know inquiries and reports alone don’t make things right. We need to bring the entire society with us, help them see what’s actually happening and help them want to see these changes happen.

"An easy comfort resides in shaking your fist at the foreign monster on your plasma screen while ignoring the monstrousness done right here." @chakrabortty on the cruelty of indefinite #detention and the #HostileEnvironment here in the UK.https://t.co/01uSPctg7B

— TheDetentionForum (@DetentionForum) June 27, 2018

And this takes me back to my starting point, my old, beaten-up copy of the Committee report. Reading the report again, I find so many things about asylum and immigration system that haven’t changed. There was one thing I did not do 12 years ago, and that was to engage politicians, engage others and engage communities and work with them towards the same goal. I now see so many opportunities for people to get more active in working with migrants to demand a fair and humane society for everyone.

Below are some of the activities you can get involved with right now – the tweets will take you to relevant webpages that suggest action you can take.

Don’t be like me 12 years ago, who read the report, put it on the book shelf and walked away.

Around 30, 000 people are detained in the UK every year – taken from their friends, families, communities and support structures.

Yet communities are fighting back and saying ‘enough’. They are saying "#TheseWallsMustFall".

Take action today: https://t.co/foTsw1s47Q

— These Walls Must Fall (@wallsmustfall) June 26, 2018

Our Govt rips families apart and destroys people's mental health by holding them in immigration detention indefinitely. Today we've launched a toolkit so you can help end indefinite detention, whether you've got 30 seconds or a whole day. Take action now! https://t.co/EspnjyPRAv pic.twitter.com/9tvuu0pzxy

— Liberty (@libertyhq) June 25, 2018

Since the start of the 'hostile environment' for immigrants, MPs have reported *their own constituents* to the Home Office hundreds of times. Our new campaign with @MigrantsOrg is calling on all MPs to sign the #MPsNotBorderGuards pledge. Take action: https://t.co/mOxRF83B31 pic.twitter.com/NWaFehyaw0

— Global Justice Now (@GlobalJusticeUK) June 21, 2018

Eiri Ohtani @EiriOhtani

Project Director, The Detention Forum